Ema Shin | Hearts of Absent Women

Exhibition

-

Hearts of Absent Women #5

Vendor:Ema Shin45 x 72 x 10 cmRegular price $7,500 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Hearts of Absent Women #11

Vendor:Ema Shin46 x 60 x 10 cmRegular price $5,000 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

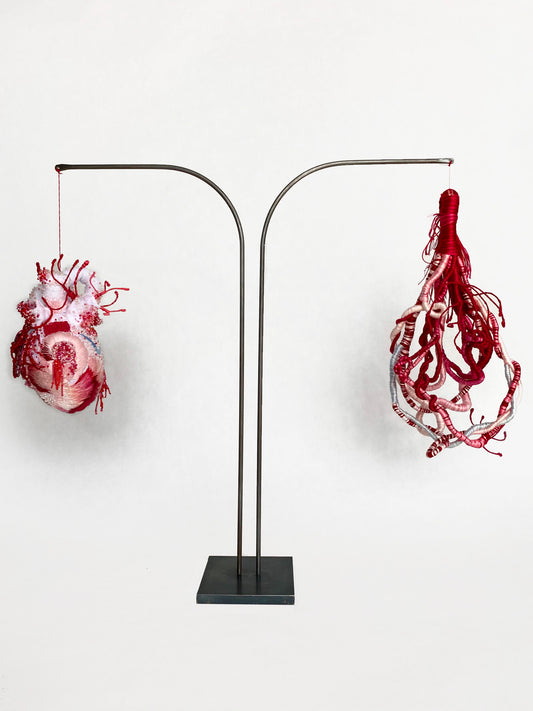

Hearts of Absent Women #13 & #14

Vendor:Ema Shin60 x 50 x 11 cmRegular price $5,000 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Hearts of Absent Women #7

Vendor:Ema Shin62 x 40 x 20 cmRegular price $5,500 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

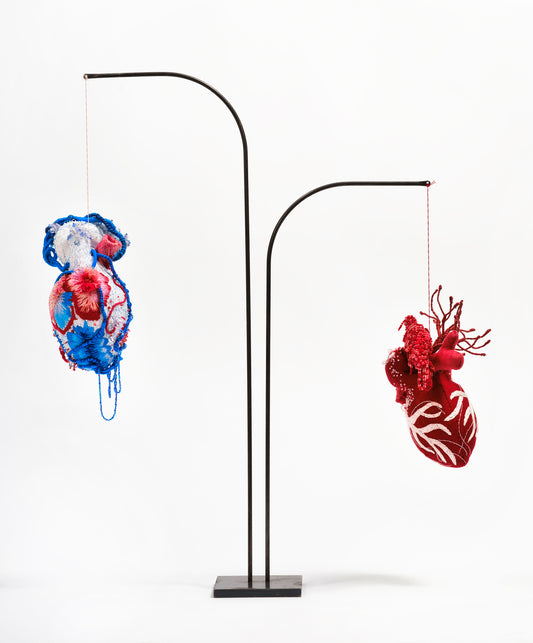

Hearts of Absent Women #15

Vendor:Ema Shin71 x 58 x 18 cmRegular price $6,000 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Hearts of Absent Women #12

Vendor:Ema Shin81 x 40 x 26 cmRegular price $9,000 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Soft Alchemy (Tree Girl)

Vendor:Ema Shin64 x 30 x 3 cmRegular price $4,500 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Soft Alchemy (My Pelvic Bone)

Vendor:Ema Shin50 x 42 x 3 cmRegular price $5,500 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

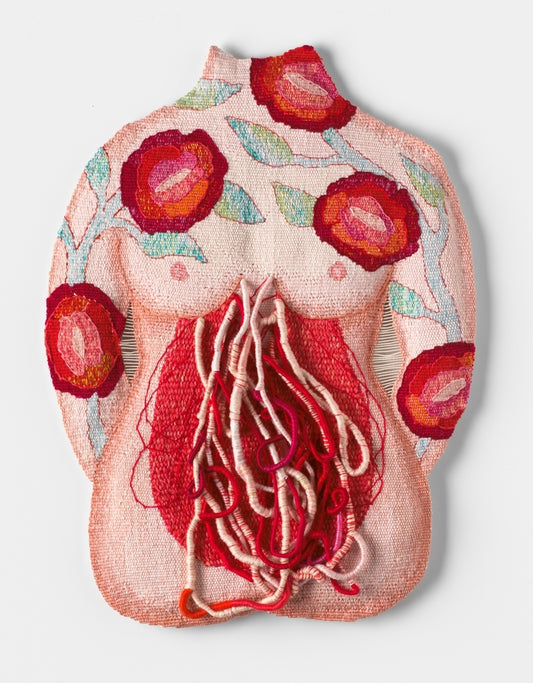

Soft Alchemy (Mother)

Vendor:Ema Shin55 x 42 x 4 cmRegular price $6,000 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Soft Alchemy (Fertile Heart)

Vendor:Ema Shin54 x 80 x 6 cmRegular price $8,900 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Soft Alchemy (womb for everyone)

Vendor:Ema Shin190 x 156 x 7.5 cmRegular price $22,000 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Hearts of Absent Women #8

Vendor:Ema Shin36 x 68 x 10 cmRegular price $6,500 AUDRegular priceUnit price / per

About

Ema Shin | Hearts of Absent Women

There are many reasons artists make work. It can be an expression of new perspectives, a means of storytelling and sharing, or is born from a compulsion to create. For Ema Shin, it is a combination of all three. Through the process of artmaking, Ema challenges deeply entrenched cultural narratives in order to express her agency, place and voice. Her compulsion to create is informed by the artist’s lived experience as a woman, migrant and mother, and the intersecting forces of casual racism and sexism that have informed her place in the world.

This is a narrative that is familiar to me: as Asian women we are often socialised to perform particular expressions of self, and questions of femininity and gender double standards are complicated with additional cultural expectations. When I spoke with Ema over Zoom during one of Melbourne’s many lockdowns of 2021, she emphasised the importance of artmaking as a ritual of mental care and routine during turbulent times, but also stressed how anger can act as a great motivator to create. Growing up in a male-dominated family in a patriarchal society, where the names of female relatives are not recorded, Ema’s practice acts as a means of affirmation – wielding the power of cultural stories into powerful expressions of femininity.

Though this expression is compelled by anger, to encounter Ema’s works is to enter a world guided by warmth and care. Working primarily with bright hues of reds, oranges, and pinks; it is easy to draw comparisons in her palette to that of the fleshy inner body. The softness and tactility of the materials furthers this reading. The colours are also a form of good fortune that honours the colours and motifs of Korean folk art. In the same way that works made by women tend to be historically forgotten, Korean folk art was produced by ‘unknown’ artists. These artists are not unknown, however, they are just unnamed. In Ema’s hands, the care and labour she places on each individual embroidered heart is an act of remembering, a way of expressing and memorialising the hearts of women who came before.

There are many reasons artists make work. It can be an expression of new perspectives, a means of storytelling and sharing, or is born from a compulsion to create. For Ema Shin, it is a combination of all three. Through the process of artmaking, Ema challenges deeply entrenched cultural narratives in order to express her agency, place and voice. Her compulsion to create is informed by the artist’s lived experience as a woman, migrant and mother, and the intersecting forces of casual racism and sexism that have informed her place in the world.