Ian Friend

By Lucy Stranger

What prompted your move to Australia?

I was working as a curator at the Tate Gallery, and John Walker was exhibiting at the Tate and the Hayward Gallery. He was the Dean of the School of Fine Art at the Victorian College of the Arts in Melbourne at the time, and I asked if there was any chance of coming to Australia, as I would like the opportunity. I received a phone call a few months later offering a year in residence and teaching. I could have taken a year’s leave of absence from the Tate, but I had a feeling and just resigned. I was ready for a change.

What was the effect of moving from the soft light and landscape of East Sussex to the wide expanses of Australia?

I tried too hard to fit in to begin with, and it didn’t work. I am now Australian but I grew up as a landscape artist in England. East Sussex is rolling hills; it’s a Cretaceous landscape, and it’s built up over millennia. It is a coastline that is being constantly eroded; the South Downs is chalk, basically soft-shelled animals. Where it reaches the sea is where I lived near Beachy Head. I used to go out with my backpack and watercolour sheets and sit and paint the landscape. That was before I went to art school; then I later became interested in conceptual and abstract art.

Who introduced you to art?

Miss Johnstone, and it took me years to pluck up the courage and call her Phyllis, as she was very austere. She moved into the farmhouse cottage next to us. I always drew, and she looked at what I did and said that if I wanted to come and work with her that was fine. I walked into her studio and I thought I’d died and gone to heaven. I was eight and she took me under her wing and nurtured my career.

You initially trained as a sculptor; what drew you back to drawing?

I made sculpture but I think the thing that has always driven the work is drawing. I’d draw for a sculpture, and I’d think I don’t really want to make it. The actual physical work I did not mind, but it was different. With drawing you can imagine an object and put it into an imaginary space. This was at a time when conceptual art was very strong. I was very drawn to Arte Povera, to the conceptual, and just working with paper and it all seemed to fit. The desire to make objects faded.

Do you always move from small to large scale?

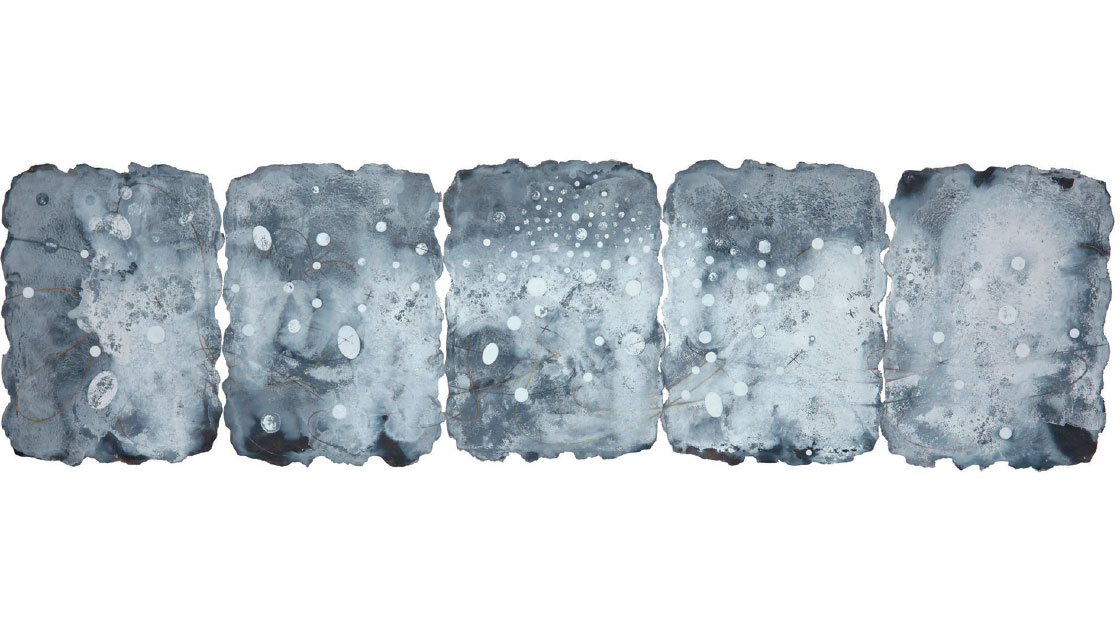

One of the reasons I like working from a small size to a larger size like this is that it constantly challenges me. You don’t get into a comfort zone, the cross-referencing is a challenge. Once you work up to the larger size, things start to happen with manipulation of flows of gouache or ink that is quite difficult to control. Chance comes in a lot more with the bigger works.

Works on paper tend to be seen quite often as studies towards something else but I see the works on paper as finished works in their own right. Michelangelo used to do studies but would also do presentation drawings, very finely detailed for a client.

I love paper. I like to work with different papers as each paper has its own quality. And how pigments and a drawn line react to a sheet of paper can be really quite different at times. There are some works that are on vintage Whatman paper. I have always been fascinated with the handmade sheet, the artisanal quality of it. The paper is as much a part of the work as what becomes manifest on it. I am very particular about the technical side of things; they have to be constructed properly. There is nothing haphazard about the methodology, but what can happen can be quite surprising sometimes.

Working within set rules opens up potential for greater possibilities?

Exactly. I like the idea of art being a rule-governed activity. I set up certain divisions on the sheet and decide how to operate within those. But within that you can see there is so much variation within tone with the washes, I wash it back and put on another layer repeatedly. After that I start to impose geometry through the drawn line.

There is a lovely cyclical process of adding and taking away.

Yes, it is all about addition and subtraction, and then gradually moving towards some sort of resolution through the geometry and linear structure.

When do you know when a work is finished?

It can go on for weeks until I feel a resonance. It’s a kind of layering that offers more than what you can see immediately. I think what also is important is when macro and micro elements are synchronised. You are looking through a magnifying glass, and you are also looking out through the universe.

What informs that celestial outlook?

I am really interested in the culture of mid-17th-century Holland; it is the beginning of the Age of Reason, the Age of Enlightenment. A philosopher I am re-reading at the moment is Baruch Spinoza, who was excommunicated from his synagogue in Amsterdam for questioning the Bible as the word solely of God and questioning the notion of miracles as they cannot be explained as natural occurrences.

Scholarship indicates that Johannes Vermeer painted Antonie van Leeuwenhoek as the geographer and the astronomer, and the emphasis here was that we are simultaneously looking at the earth and also looking out at the celestial spheres. This was the beginning of a more sophisticated science, looking into the finer elements of the microcosm of our world. All this condenses into an intense cultural brew in the context of 17th-century Holland. The kind of thing I am doing now relates more to that rather than anything particularly contemporary.

With your works you can get lost in that sense of the expanse and the infinite.

Yes, even on a small size it can have a sense of scale that extends beyond the physical limitations of the sheet.

What role does music play in your work?

I have always been interested in music; we had a piano in the house and my mother was quite a good pianist. Sometimes you just sit and listen, or you sit and look and let that permeate your consciousness. That big box behind you is full of Mozart. I always felt Bach was the greatest composer, then I thought I should really listen to Mozart, and I have this box set of the complete works of Mozart – 225 CDs – and I’m half-way through it.

Do you see your works as marking points in time in your life?

Yes they refer to things I’ve read. Joy At Death Itself refers to The Oval Window by JH Prynne, a poet who has been a real touchstone for me. Some of the titles are taken from what I have read or have listened to a particular musical piece. Angel Song is from a jazz CD by Lee Konitz and Kenny Wheeler – the way that it flowed was like washes moving through space.

In your recent survey exhibition at Andrew Baker, ‘Musæum – Fragments of Former Worlds (Works from 1983–2016)’, what was the significance of the title?

It was a label in the Victoria and Albert Museum in the display of meteorites that referred to former worlds as told by Jacquetta Hawkes in her 1951 publication A Land. It’s like digging back into the past, which is what geology and archaeology are. The work that I am doing now is really some sort of resolution of younger experiences transformed by the dislocation of time and geographical distance.

How conscious are you of time in your work?

I am a slow worker. I don’t want to sound morbid but this year I have had so many friends and two close relatives die that I don’t know if I am subconsciously speeding up. You become more aware of your mortality. I am coming up to 67 and I still don’t really know anything, I just know a bit. I am reading a lot more, I get up in the morning at about five o’clock, and I just start working and reading and I might be going until night. I have eliminated the protestant guilt of taking time off to read.

I’ve just read a really good biography by James Stourton of Sir Kenneth Clark, and one of the things that Clark says about older artists is that some of them ‘live in a state of isolation, holy rage and transcendental pessimism’ (laughs) and I thought that’s me …