Dena Kahan’s painting practice aims to subvert our natural inclination for order and perfection.

Using museum collections as subject matter for still life painting, such as the world famous collection of glass botanical specimens in the Harvard Museum of Natural History, Kahan introduces ambiguities of scale, space and reflection to undermine the clear containment of the museum case. In doing so, she transforms museum objects into a kind of substitute romantic landscape, hinting at the awe of the natural world.

Working with thin layers of oil on linen, resulting in delicate and translucent surfaces, Kahan’s application of paint keeps the focus upon the materiality, reflecting the delicate nature of her subject matter. Her paintings segue neatly into the art museum environment, evidenced by the survey exhibition of her work at Ballarat Fine Art Gallery in 2014.

In the below interview, we are delighted to share some insights into Dena's fascinating studio practice.

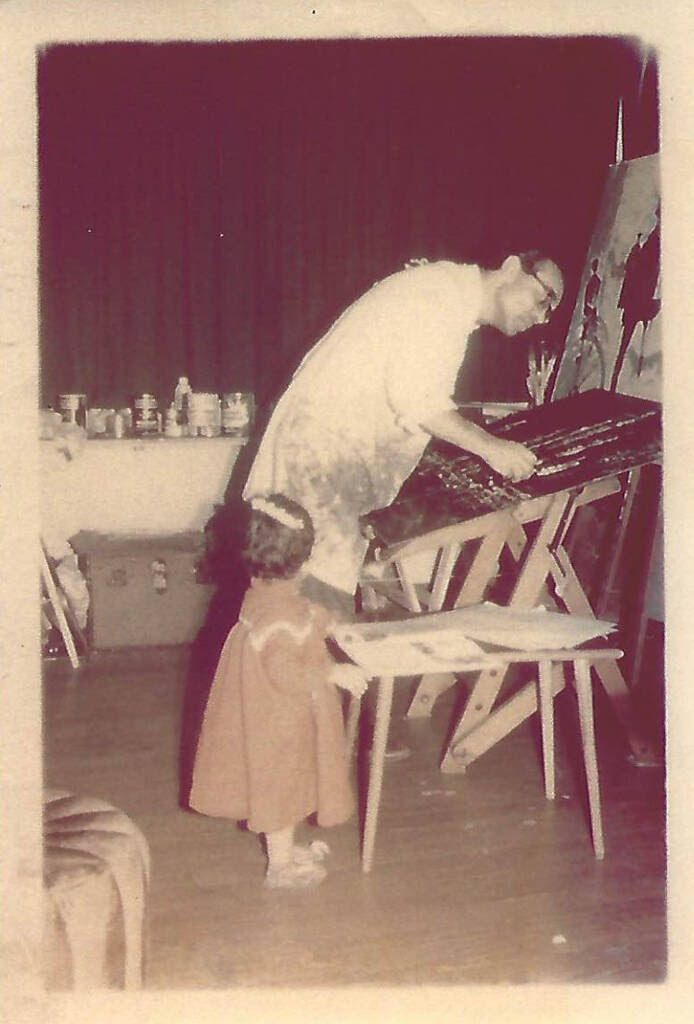

GS: Let’s begin with your childhood. Your parents mixed in artistic circles of the avant garde in Melbourne in the 50s, 60s and 70s. What was it like being the daughter of an artist?

DK: I've never thought of my parents that way, as being part of the avant garde - but yes, they did mix a lot with artists, singers, writers... They met lots of people through my father Louis Kahan’s portrait work and his stage and costume design for the opera. My sister and I used to sit in my father’s studio with him and draw the life models when we were little and we often met people who came to have portraits made. .

GS: For several years your compositions have included antique botanical models from museum and university collections. What attracted you to this subject matter?

DK: I discovered the botanical models many years ago via my conservation work. I encountered them whilst I was a conservator at Melbourne University and did a survey of the Herbarium collection. I saw these fabulous papier mache models of plants and parts of plants, much larger than life size. They had a surreal quality which fascinated me.

It was only years later that I came back to these models. In the meantime, I left conservation and went on to work for several years on series based on glass museum collections. The V&A decorative glass, then series based on glass models of marine animals and the famous ‘Glass Flowers' at Harvard Natural History Museum in Boston, which I visited and photographed. The glass models were made in the 19th century by Bohemian father and son Leopold and Rudolf Blashcka. These paintings were very complex compositions, playing with scale and space and reflections.

Having explored the transparency of glass for several years I finally came back to the first solid botanical models in the Herbarium at Melbourne University. Since then I have gone to many places, including Sydney, Edinburgh and Cambridge to source more models and museums. Curators have always been very generous in allowing me access to these fragile objects, for which I am grateful.

I have always been interested in our relationship with nature; our desire to control and order it. The natural history museum interests me as metaphor for this desire to control and classify. In my paintings, the order of the museum is undermined. Labels are illegible; the surreal theatricality of the models overwhelms their role as objects of scientific certainty. Parts of the models often resemble sexual organs, which of course is what flowers are. Sometimes I don't realise this until the painting is finished, but I love this playful and slightly disturbing element. I don’t want my paintings to be simply beautiful. I like them to contain surprises and to be a little ambiguous and unsettling.

GS: Your painting surfaces are delicate and almost translucent. Can you tell us a little about your process?

DK: I mostly work from photographs I take myself. And because I document objects in museums, I have little control over the circumstances or environment. There is always an element of randomness, which I then have to work with. I am not a skilled photographer. I concentrate on composition and colour. In fact, I like to use the flaws in the photographs as part of the painting. The flares and out of focus areas become part of the work. I don't project or square up the image on the canvas, but draw it free hand. So, the work is not an imitation of the photograph but an interpretation into the medium of paint. Every time I use a photograph I see different things and create a different painting. It is a subjective process.

The glass paintings really challenged and developed me technically; learning to master the art of painting intricate transparent objects and reflections. I discovered very smooth oil primed Belgium linen and learnt to paint very thinly. These works did not allow overpainting, as this lost the effect of transparency and the white of the canvas coming through. So I had to finish whole sections in one day, wet in wet. People often mistake these paintings for watercolour, but I almost always paint in oils. I love the luscious, slippery, sensuous quality and smooth transitions you can only achieve with oils. There is a physical pleasure in handling oil paint, which I hope is visible in the paintings. The more recent paintings of solid paper mache models are more forgiving, allowing a few corrections and over painting, but the technique of painting wet in wet, and whole sections in one sitting has become a habit for me. So, unfortunately has the double-primed Belgium linen, which is awfully expensive.

GS: In your new exhibition, Hothouse, insects infiltrate the sterile environment of the museum storeroom, in imagery which references the tradition of 17th century Dutch still life. Tell us more..

DK: I have always admired those wonderful 17th century Dutch still lives, many painted by women. Botanical subjects and the study of botany were areas allowed to women and associated with femininity. However, these paintings are not merely beautiful. They contain symbolism and metaphor. Flowers were symbols of transience, mortality. Some have religious significance. In these paintings, flowers from different seasons bloom together. So time is alluded to in this way. The flowers are fragile and sometimes show signs of decay, and yet the paintings live on. Insects could symbolise the purity of the spirit or its corruption. The botanical models I paint are also paradoxical objects, at once natural and artificial; fragile and enduring, and exist in a space between art and science. In my paintings the intrusion of insects into the hermetic world of the museum alludes to the ability of the natural world to evade our control, and also our often negative impact on the environment. In the future, perhaps already, the only evidence of many insects will be in museum cases.

GS: How have you found this period of imposed isolation? Has it encouraged you to think differently about your studio practice?

DK: I think artists are quite well suited to isolation. So much of our time is normally spent alone. So, from that point of view, work goes on as usual. I am fortunate in that I don't live alone, so I have company at the end of the day. I have had to complete some work in our garage, which is much smaller than my studio, but has good light. There have been advantages to this, being able to pop into the studio for a few minutes to make a small adjustment. It has been a good opportunity to see how it feels working from home.

More about Dena Kaha